From August 19 to September 10, Esther Schipper opens a seasonal space at PPP/Paperspace in the energetic neighborhood of Taipei ZhongShan district. The two-floor exhibition space gives the gallery just enough space to showcase each artwork. The first floor shows works by Ugo Rondinone, Andrew Grassie, General Idea, Ryan Gander, Martin Boyce, Thomas Demand and Philippe Parreno. The ground floor shows Pierre Huyghe, Ann Veronica Janssens, Roman Ondak, Gabriel Kuri and Simon Fujowara.

General Idea, Great AISD (Quinacridone Rose Deep), 1990/2019

Ugo Rondinone, small white silver green mountain (2019)

Pierre Huyghe & Philippe Parreno, A Smile Without a Cat, 2005

Installation view- works by Ugo Rondinone

Installation view- works by Roman Ondak

Installation view- works by Ryan Gander

Thomas Demand, Daily #33 (Orange), 2019

Thomas Demand, Daily #34(Lost), 2019

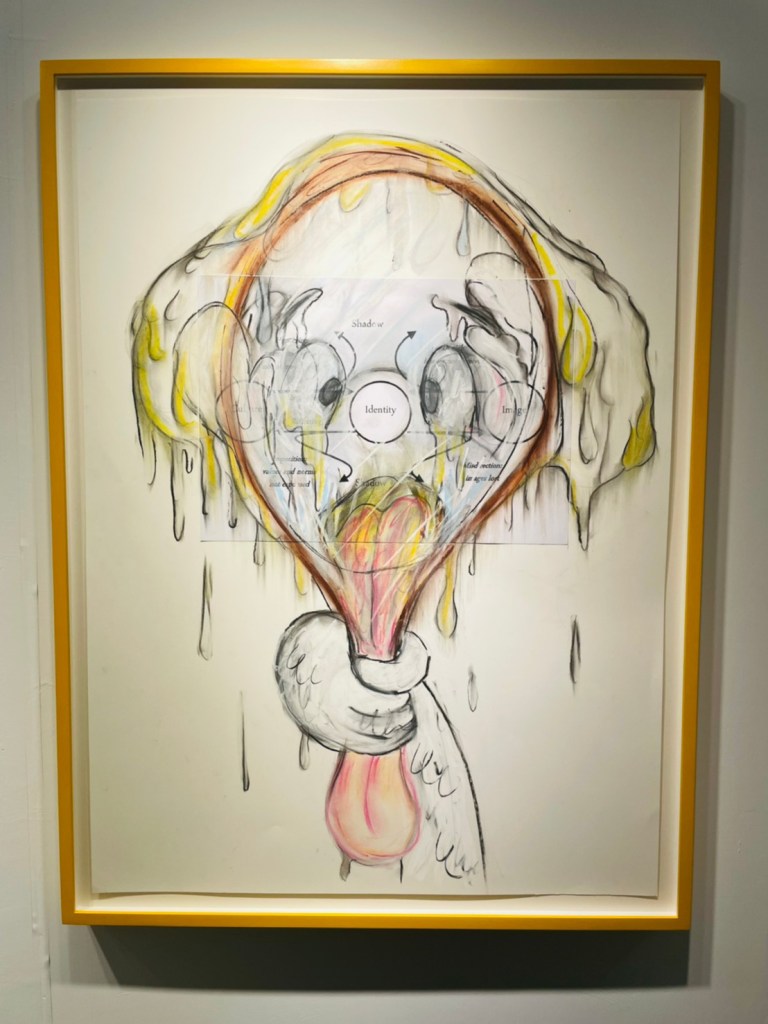

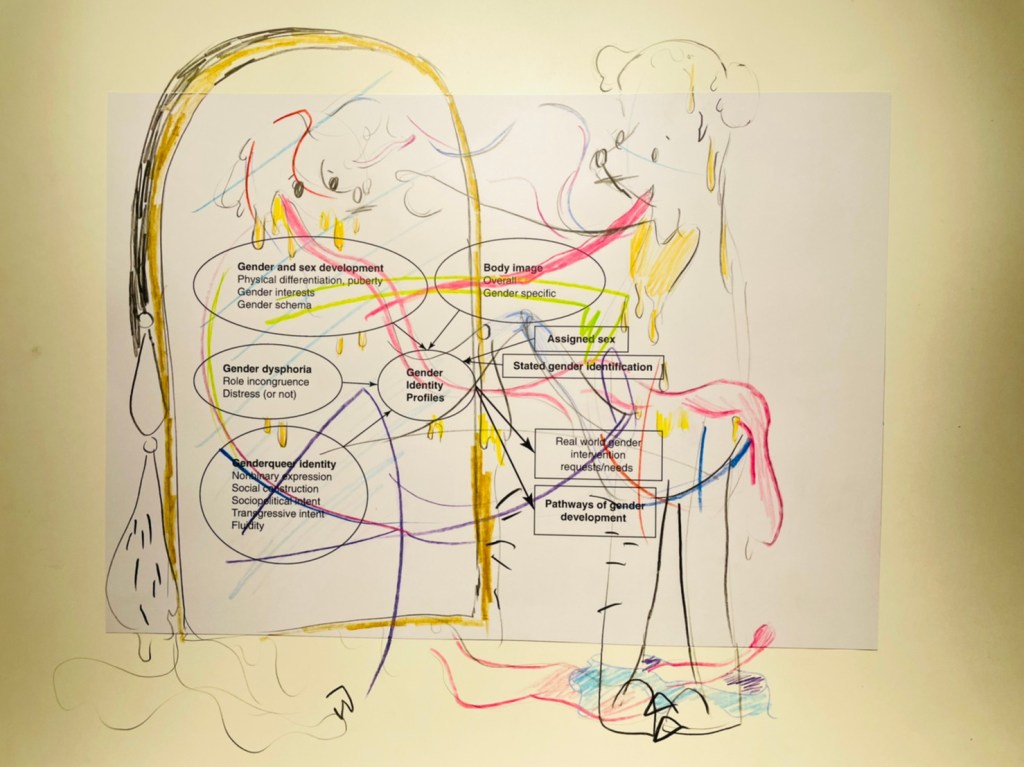

A work from Simon Fujiwara

A work from Simon Fujiwara

Ann Veronica Jassens, Untitled, 2019

Ugo Rodinone, General Idea and Philippe Parreno are not strangers to me. The gallery presents some iconic works by the above-mentioned artists – Ugo Rondinone’s fluorescent stacking rock column, General Idea’s AIDs painting and Philippe Parreno’s flickering light installation.

Ugo Rondinone (b. 1964, Switzerland)

LEFT Ugo Rondinone, small white silver green mountain (2019)

RIGHTseeiternovemberzweitaudsendundneunzehn(2019)

Ugo Rondinone, small white silver green mountain (2019)

Ugo Rondinone is a New York-based, Swiss-born mixed-media artist. His famous large-scale land art sculpture, Seven Magic Mountains (2016–2021) stood in the desert just outside of Nevada. The 32 feet (9.8m) sculpture was made from a stack of seven fluorescently-painted, car-size stones. Rondinone is represented by Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Sadie Coles HQ and Galerie Kamel Mennour (since 2017).

Esther Schipper presents two works from Rondinone. First, small white silver green mountain (2019) a portable size sculpture of fluorescent colored stacked boulders, greets the visitor. seeiternovemberzweitaudsendundneunzehn (2019), or ‘sea november two thousand and nineteen’ in English, is hung right next to the sculpture. The painting depicts the moment when the Sun sinks half-way down the sea horizon.

Ryan Gander (b. 1976, UK)

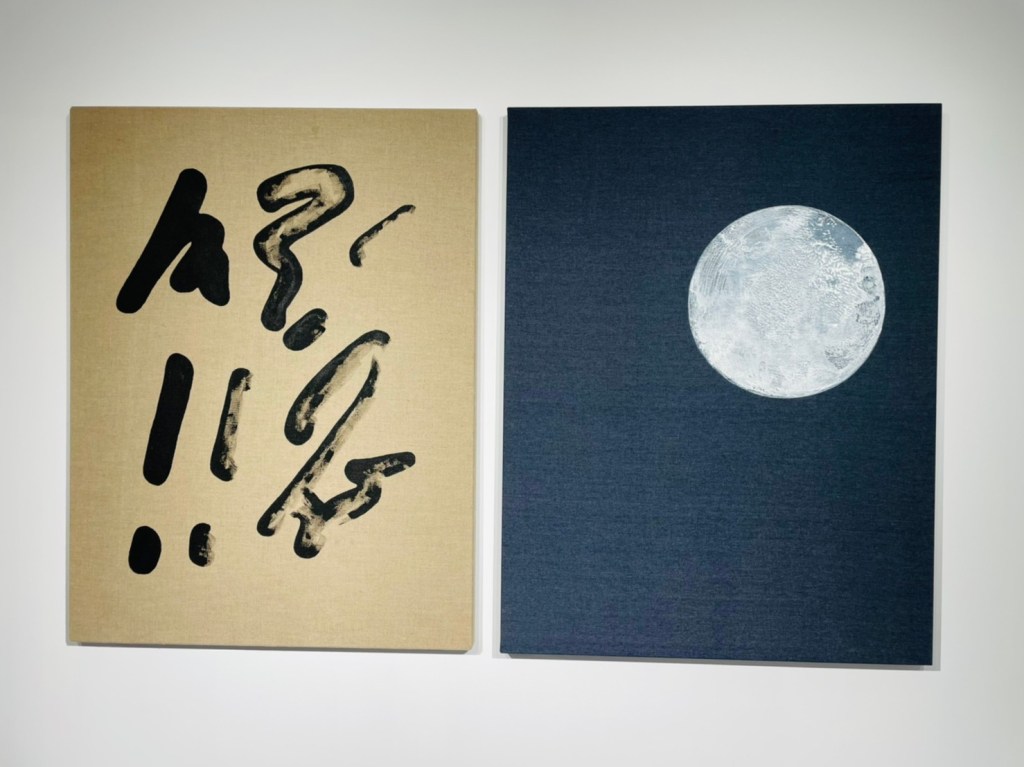

FRONT Ryan Gander, Monkey See, Monkey Do, 2019

BACK Ryan Gander, Natural and conventional signs (Some painted signage, whilst others looked up at the night sky), 2021.

Ryan Gander, Natural and conventional signs (Some painted signage, whilst others looked up at the night sky), 2021. Ryan Gander, Monkey See, Monkey Do, 2019

Ryan Gander has established an international reputation through artworks that materialise in many different forms – from sculpture to film, writing, graphic design, installation, performance and more. Gander’s work questions the language and knowledge, and investigates the modes of appearance and the creation of an artwork.

Monkey See, Monkey Do (2019) is a monotone polyurethane chair with a timed candle. The candle is set to be lit and sniffed in a set time interval. The fire and smoke add an interesting touch to the plastic chair. The composition of Monkey See, Monkey Do (2019) is reminiscent of the chair in Van Gogh’s painting, Chair (1888). Gander’s sculpture and Van Gogh’s painting both show a fire related object on a simple chair. In terms of forms, Gander’s curvy, tilted and twirled silhouette reminds the audience of the Dutch predecessor’s unique painting approach to show perspective on canvas. In the case of Monkey See, Monkey Do (2019), I thought only one angle makes the sculpture look right, looking from the outer right corner of the sculpture. Being precise in the architecture or being visually coherent is an interesting dialogue.

Ryan Gander jetted his career as an artist when he won the 2005 Baloise Art Prize at Art Basel for the presentation of his video work Is this Guilt in You Too (The Study of a Car in a Field). Gander is the recipient of many prestigious prizes and has been featured in many TV shows. Gander was featured on the British BBC channel, in programs such as The Culture Show (2012) and “The Art of Everything”(2014). The artist is currently represented by Lisson gallery, London, in the UK, gb agency, Paris, and Esther Schipper gallery, Berlin, on the continent, and TARO NASU, Tokyo, in Asia

Roman Ondak (b. 1966, Slovakia)

FRONT

Roman Ondak, Bad News, 2018

LEFT TO RIGHT

Roman Ondak, Mirage, 2017

Roman Ondak, From this Day Forward, the Desert Will Be Our Home, 2017

Roman Ondak, Desert Nuclear Explosion Watched From a Distance, 2017

FRONT TO BACK

Roman Ondak, Mirage, 2017

Roman Ondak, From this Day Forward, the Desert Will Be Our Home, 2017

Roman Ondak, Desert Nuclear Explosion Watched From a Distance, 2017

Roman Ondak is a conceptual artist from Slovakia. The artist is known for his interventions in exhibition rooms and architectural spaces, extracting everyday objects and found images and repositioning them in (sometimes participatory) installations. For example, Measuring the Universe (2007), a site-specific participatory installation, which invites the audience to note their height and visiting date on the white wall. The installation is in the collection of Tate Modern in London, Pinakothek der Moderne in Munich and MoMa in New York.

Bad News(2018) consists of a round table with three papier-mâché spheres placed on its tabletop. As is characteristic of Roman Ondak’s practice, the table, formerly a revolving worktable showing signs of wear, is a found object that most likely originates from an artisan’s workshop in Bratislava, where the artist works and lives.

In Bad News (2018), the three spheres were made from three different widely-read newspapers, the American The New York Times, the Russian Izvestia and the Slovakian SME. Ondak collected the newspaper issues for the work throughout December 2018. The diameters of the spheres were determined by the number of printed pages of each newspaper. On the surface of the sphere are random newspaper headlines and quotes. It is the observer who, subtly nudged by the work’s title, might assume “bad news” when in fact there may not be any.

Leave a comment